Gabe Collins, “Oil Dependency and Military Strategy and Deployments—U.S. and China,” China Oil Trader™, No. 9 (20 November 2012).

CHINA’S OIL & GAS SECTOR FROM WELLHEAD TO CONSUMER

Trends that give the impression of changes in reliance on a foreign oil source can be powerful shapers of policy, particularly when changing budgets and perceptions of national economic wellbeing begin shifting public attitudes regarding the merits of foreign military deployments.

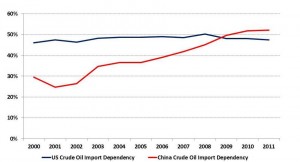

Here we speak on one hand about the U.S., where ambivalence about military involvement in the Middle East is rising in lockstep with domestic oil production gains that are trimming U.S. reliance on imported crude oil. And on the other hand, we speak of China, whose crude oil import dependency has climbed inexorably from 25% in 2001 to 52% in 2011 and whose leadership has grown assertive on the basis of a perception that U.S. power is declining.

The Bakken Shale of North Dakota, which by itself now produces roughly as much crude oil as Yemen and Ecuador (an OPEC member) combined has led the way in increasing U.S. domestic oil output. This rapid production growth, coupled by lower crude oil use, has begun to substantially trim U.S. oil import dependency, which was roughly 47% in 2011—the same level as in 2001 and continues to decline (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Crude oil import dependency of China and the U.S.

Imports as % of total crude oil supply

Source: BP Statistical Yearbook

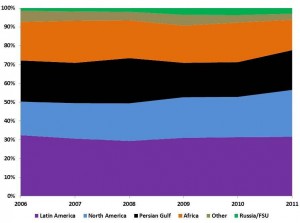

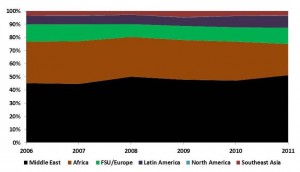

Furthermore, while the U.S. remains a large-scale crude oil importer, its barrels tend to come (1) from countries located close by within the Western Hemisphere and (2) roughly 40% of imports come from neighbors Canada and Mexico. By comparison, China pulls about 75% of its crude oil imports from Africa and the Middle East, regions rife with political instability and significant threats to oil supplies from both state and non-state actors (Exhibit 2A, 2B).

Exhibit 2A: U.S. crude oil import sources, 2006-2011

% of total imports

Source: EIA

Exhibit 2B: China crude oil import sources, 2006-2011

Source: China Customs

China too big to free ride on U.S. security guarantee

Oil supply security—especially for large industrial economies that import a substantial portion of the crude oil needs—functions a bit like gravity. It is a force field that does not always receive the attention of its more visible natural counterparts such as sunlight, but which profoundly and relentlessly influences a wide range of activities. In addition, the global oil trade model as exists today ultimately requires a military guarantor to help ensure that sea lanes can be freely and impartially transited.

The United States has played this role via stationing of air, ground, and naval forces in the Persian Gulf region for the better part of three decades. China, now the world’s second largest oil consumer and importer, has thus far free ridden on the U.S. global oil security guarantee. However, given its rising military power, increasing strategic friction with the U.S., and growing oil supply and investment ties in the Middle East and Africa, Beijing has strong strategic motives to consider maintaining a more sustained military presence in and near the Persian Gulf region.

In this vein, the port calls Chinese naval forces involved in anti-piracy missions of Somalia have made in Oman and other ports along the Arabian Sea and western Indian Ocean region carry considerable strategic meaning. Even if the PLA Navy operates outside the Persian Gulf per se, it has sustained anti-piracy operations for more than three years now in the Gulf of Aden, which lies near key Asia-bound oil supply routes. Presence brings influence and Beijing is presumably well aware of this.

China’s naval activities in areas bordering the U.S. CENTCOM and AFRICOM areas of military responsibility under the auspices of protecting shipping reflect a quiet, but assertive move that Beijing would have been unlikely to take and sustain in the absence of Chinese dependence on oil imports sourced from the region. These moves by no means signal conflict between the U.S. and China—they simply reflect that a rising naval power and oil importer no longer wishes to entrust its oil supply security to an outside power with a worldview that is frequently divergent from Beijing’s. Chinese leaders recognize that naval forces in the region multiply the influence already flowing from Chinese entities’ growing diplomatic and financial investments in the region.

Chinese actions on the oil security front speak much louder than words, for in China, oil and energy security receive much less attention in official statements regarding military posture and strategy than they do in the U.S. For example, the 2002 White Paper on China’s National Defense mentions the world “oil” twice and the word “energy” four times. In the 2010 edition, there were no mentions of “oil” and 13 mentions of “energy.” In contrast, the 2002 U.S. National Security Strategy (NSS) did not mention “oil” and had eight uses of the word “energy.” In 2010, the NSS only used “oil” twice but mentioned the word “energy” 48 times, suggesting that the issue is, at least on an openly stated basis, a higher priority in U.S. defense policy making than it has been for China.

Despite the dearth of public discussion explicitly linking rising oil import dependency and naval modernization, it would be unrealistic to interpret this as meaning that China has simply decided to “rely on the market” as a primary oil supply security approach. Indeed, a wide range of Chinese oil market behavior—such as building up a tanker fleet and creating world-scale oil trading companies—suggests that Beijing tends to be most comfortable relying on the market when it has the muscle to shape events in its favor, should the need arise. Ultimately, the rawest form of this muscle is the PLA Navy, which is benefitting from a world-class military shipbuilding program that now sees Chinese yards simultaneously working on six different classes of modern submarine and surface warship.

Even as the PLAN becomes more capable in coming years and potentially expands its operations along China’s maritime energy supply lines, Beijing is unlikely to expressly link naval modernization to oil security concerns simply because it does not need to—naval power is fungible because the same warships that can show the flag along tanker routes can also fight pirates, influence diplomatic negotiations with regional neighbors, and perform myriad other tasks.

Key Security Implications

1. China’s crude oil import dependency will almost certainly continue rising over the next three years. Chinese companies and their foreign partners need at least 2-3 more years to commence commercial development of the country’s largely uncharted shale gas (and possibly oil and liquids) reserves. Beyond this point, if Chinese explorers find oil in addition to gas, we would not be surprised to see an additional two years of development drilling before the fields could substantially impact China’s oil import balance.

China’s initial shale wells have all been gas producers and only time and the drill bit will tell if the country has its own edition of the Bakken Shale. This means that for the next 3-4 years, China’s oil import dependency will almost certainly continue rising, and with it, leadership concerns about vulnerability to price shocks and supply shortages triggered by disruptions to crude oil supplies—particularly out of the Middle East and Africa.

2. Rising oil import dependency is likely to make Beijing more supportive of offshore drilling with China, which risks inflaming maritime disputes with Japan, Vietnam, and the Philippines. The prospect of substantial offshore energy resources plays a key role in the maritime disputes between China and its maritime neighbors, especially in the South China Sea (SCS). Exploration drilling in deepwater areas of China’s undisputed exclusive South China Sea economic zone by Husky Energy, CNOOC, and BG Group have yielded significant natural gas finds. This suggests the area has real potential to become a substantial natural gas supplier for China’s Southeast Coast and has whetted energy companies’ interest in other zones of the SCS.

The international majors are likely to be reluctant to engage in deepwater exploration activities outside of China’s undisputed EEZ, as doing so could expose them to Beijing’s displeasure and affect their business prospects in China. For example, when the Philippine government auctioned exploration blocks in July 2012 including areas claimed by China, not a single large global oil & gas company submitted a bid. Given that the maritime disputes are unlikely to be solved anytime soon, the practical result is that the only way international exploration funding and expertise will flow into disputed areas is if CNOOC chooses to operate there and brings in foreign partners.

3. China will continue maintaining a naval presence in the Western Indian Ocean. The Gulf of Aden anti-piracy mission has given China its first forward deployed military assets, which have proved useful both in a broad strategic sense and for specific missions. In February/March 2011 Beijing deployed Xuzhou, one of its most modern missile frigates, to help provide security for the evacuation of PRC citizens trapped in Libya. Xuzhou was useful in the Libya contingency because it was already forward deployed as part of China’s anti-piracy mission in the Gulf of Aden.

With this firsthand lesson in how useful forward deployed military assets are for a country like China that has increasingly global interests, there is a strong likelihood that China’s civilian and military leaders will seek to maintain a more sustained presence in the Indian Ocean region, perhaps making port calls inside the Persian Gulf as well.

About Us

China Oil Trader™ strives to provide a holistic, globally-oriented analysis of Chinese oil and gas issues. In doing so, we often view multiple classes of commodities simultaneously and assess how they interact with each other. Our ultimate goal is to provide a focused source of fresh, creative, and anticipatory research for policymakers, investors, and others interested in China’s development as an energy and commodity superpower.

China Oil Trader™ founder Gabe Collins grew up in the Permian Basin and has experience dealing with energy issues for both the U.S. government and as a private sector commodity analyst. He speaks and reads Mandarin, Russian, and Spanish. Gabe has published numerous oil and gas analyses in outlets including Oil & Gas Journal, The Naval War College Review, Orbis, Geopolitics of Energy, Hart’s Oil and Gas Investor, The National Interest, and The Wall Street Journal China Real Time Report. Gabe also co-founded the www.chinasignpost.com analytical portal. He can be reached at gabe@chinaoiltrader.com.