Special Guest Contribution

Arthur Rodrigues, “Oil & Gas Bidding in Brazil and Opportunities for Foreign Investors,” China Oil Trader™, No. 11 (19 December 2012).

CHINA’S OIL & GAS SECTOR FROM WELLHEAD TO CONSUMER

Much is discussed about how China is investing in agriculture and mining in Brazil and South America, but little attention is paid to future (and current) opportunities in both O&G and energy. Earlier this year, for example, the State Grid Corporation of China bought around 2,792 km of power lines in Brazil; yet, so far, Chinese oil companies prefer not to operate in exploratory areas in the country. In contrast to many places where China directed its resources, Brazil is an investment grade country with solid protections for investors.

Two important investments opportunities are coming in 2013. The first one and arguably the most important is the bidding for new areas for O&G exploration in the concession regime., Brazil has not had a bidding round since 2008, and the government recently announced plans to bid areas in several states in the so-called 11th Round. The second opportunity is the bidding for the Pre-Salt area, a region that is well known for huge O&G reserves. I will primarily discuss the first opportunity, as the second will only occur late next year or in early 2014. States that are going to have areas for bid include Maranhão, Ceará, Espírito Santo, Amapá, Pará, Piauí, Rio Grande do Norte, Bahia and Alagoas. It is certain that the area made available will be bigger than several countries combined. In an early estimate, the Ministry of Mines and Energy disclosed that more than 122 thousand square kilometers will be available.

Figure 1: Areas to be made available

Picture taken from: http://www.amchamrio.com.br/download/palestras/2011/1485_MagdaChambriard_ANP.pdf

O&G exploration in Brazil was liberalized in 1997 and has so far had 10 “Rounds” for general areas and 2 rounds for marginal fields. In Brazil, the federal government owns the areas and bids them in a public bidding procedure. There was high anticipation for when the next round would be held, since the 10th Round – the last one – was offered in 2008. As mentioned, the government announced the 11th Round for early next year. However, China is already well established in the sector in Brazil. For example, Sinochem has partnerships with Statoil in offshore areas at the southeast part of the country, while Statoil remains the operator.

Why this huge gap between 2008 and 2013? Just following liberalization, Brazil had only one exploration regime: public concession. Bidders would bid for an area and were they to win, they would have a concession for a period of time. They would own the oil subject to regulations by the ANP – the Brazilian National Agency of Oil, Gas and, lately, Biofuels. However, in 2007 Petrobras (Brazil’s NOC) discovered the “Pre-Salt layer,” huge reserves in deep water, before the salt layer. Immediately, the government suspended all biddings in the areas and created a new regulatory framework specifically for the Pre-Salt area.

Currently, the “old” system still exists, but the Pre-Salt area has an independent regime. For the Pre-Salt, Petrobras is the only operator and other companies must work in cooperation with this company. Additionally, for the area, there will be no concessions regime, but a production sharing regime. The government announced the bidding for the area for late next year. For now, I will discuss the old regime as it is how the areas will be made available early next year.

Economics

Brazil certainly has advantages when compared to other countries in the world taking into account political and economic stability, enforcement of judicial decisions and arbitral awards, regulatory framework, transparency, and reserves. Government take in Brazil is minimal compared to other countries and (currently) there are no restrictions on oil exports. Despite the fact that the government has room to maneuver and restrict rights, those powers are never, and have never been used. Brazil has more than US$ 370 billion in financial reserves, an economic monster compared to the US$ 45 billion of its neighbor Argentina.

Brazil has more than 14 billion bbl of proven oil reserves and 423 cubic meters of gas reserves. 38 national and 36 foreign companies are already in the business.

However, the bargain ends there. There is a joke around the market that to be a service provider in the country is a great business, but to be an operator is hardly a business. Getting a drill and renting equipment can be extremely expensive, and investors should not expect to go there without a sound business plan that takes into account such costs. Additionally, differently from many other Latin American countries, human resources are also expensive, rare, and with high turnover. On the bright side is the fact that getting a working permit is merely a matter of paying fees.

But, making use of foreign labor can hinder your local content mandates (discussed below). It is possible to get a block (i.e. an exploratory area) without bidding exorbitantly in local content, but that is not seen in practice. In practice, firms bid the highest number possible to win, expecting little enforcement of the rules. Some firms bid 100% (before Round 7), even knowing that it would be impossible to fulfill this requirement. Therefore, another important part of an investor’s business plan is how to deal with local content on goods and services.

Finally, competition could be a problem. Petrobras controls a substantial amount of the market and there are many opportunities for the company to exert market power. It is well known that Petrobras deals with providers with an iron fist, sometimes “convincing” them to maintain a price or supply to Petrobras. That could help explain why Petrobras is so prevalent as an operator in many fields.

General Framework

The main legislation on the area is Law nº 9.478/97 (you can find its entire content in Portuguese here http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L9478.htm), but Constitutional provisions are also relevant. ANP is the main regulator and is the entity that coordinates the Rounds. A Round is a bidding procedure that each time has different blocks and priorities. For example, the 7th Round was known as the “Gas Round.”

To participate as an operator, a company must open a subsidiary in the country (mere authorization to do business in the country is insufficient), and pass a technical and economic test, a previous step in the bidding procedure. Since liberalization, no restrictions exist for the investments made by international companies, and major players are in Brazil such as BP, Repsol, Statoil, and Shell. However, Petrobras still wins the majority of bids and some companies prefer having partnerships with Petrobras as an operator.

Opening a subsidiary in the country means acquiescing to Brazilian law, and although the concession contract provides arbitration, both substantive and procedural law and the place of the arbitration are local. However, Brazil’s arbitration law is not so different from international standards, especially the New York Convention (of which Brazil is a signatory). This step requires time and if an investor company is planning to invest for the next year by itself, it should hurry and get things done now. Obviously, an attorney would be necessary and firms in Rio de Janeiro are the best suited for the job. São Paulo is the capital markets city of Brazil, whereas Rio concentrates on the O&G industry.

The public tender protocol (i.e. the regulations for the bidding) are still not available, but aside from royalties and participations distribution (which does not affect an investor decision), it is most probable that the regulations will be the same as Round 10 for Round 11. The basic rules for that Round will be explained here, but as said, they can change. If you are brave enough, check both documents available in English:

Tender Protocol: http://www.anp.gov.br/brasil-rounds/round10/arquivos/editais/FT%20Protocol%20R10%20Final%20Version.pdf

Final contract: http://www.anp.gov.br/brasil-rounds/round10/arquivos/editais/Conc_agreement%20R10.pdf

From the publication of the offered areas to the signature of the concession agreements, an investor can expect at least seven months, but from the publication of the offered areas to the bidding process, the time is usually less, around three months. However, it is customary for the ANP to provide a draft of the tender protocol and the contract before the official ones are published. There are public discussions regarding both documents, but the Instituto Brasileiro de Petróleo, Gás e Biocombustíveis (IBP) has an important role as the main association of the sector. Independent companies sell information about seismic that was previously done in the areas that are supposed to be offered.

As mentioned, the initial phase, “qualification,” is the bureaucratic part, in which the company must prove it is capable financially, technically, and legally to take the project. An operator can be graded as A, B, or C, which limits their ability to bid on blocks offshore or inshore according to grade. The government tries to prevent small companies from obtaining areas only to resell them later or to prevent ill equipped companies from being able to effectively work on them. There are very few restrictions on companies which are not going to be an operator. If you qualify for one Round, there is an easy transfer of documents to another Round.

After paying a fee (“participation fee”) and before the bidding, companies have an opportunity to analyze the data available. Any seismic material conducted by companies is ANP’s property, but interpretation on the material is public.

Now for the biddings: how much should I pay to get a block? How does the government decides who is going to win? There is an interesting aspect of all this: the ones that pay the most will not always win, and that has happened in the past! The winners in the bidding procedure are awarded with the areas when they get top marks in three elements:

Local Content (20% of the grade)

Minimum Exploratory Program – PEM (40% of the grade)

Signature Bonus (40% of the grade)

Theoretically, it is possible to win paying very little money and offering very little local content. In practice, however, bidders tend to bid the maximum possible in local content and make a mix of PEM and bonus.

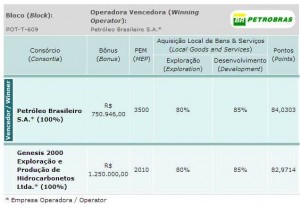

Figure 2: Example of a second place company that offered more money than the winner but lost because it did not offer enough PEM

Available at: http://www.anp.gov.br/brasil-rounds/round10/resultados_R10/resultados_SPOT-T4.asp

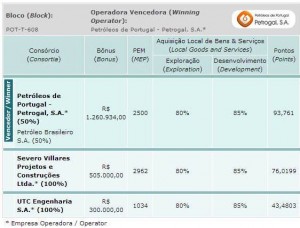

Figure 3: Opposite from above. Second place offered a lesser bonus but more PEM and lost

Available at: http://www.anp.gov.br/brasil-rounds/round10/resultados_R10/resultados_SPOT-T4.asp

Local content represents the amount of goods and services an investor would have to buy from Brazilian providers for that specific country. ANP has a detailed spreadsheet on the expected amounts, but since Round 7, there have been minimums and maximums of local content as well. Normally, onshore blocks demand higher minimums of local content, while offshore demand less. Additionally, blocks in the exploratory phase demand less local content, whereas ones in the development phase require more. In Round 10, the minimum local content for the exploratory phase of the onshore blocks was 70%, and the maximum 80%.

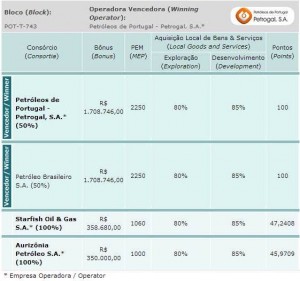

Figure 4: Example of how companies tend to bid at the maximum in local content and how the dispute is, in fact, with PEM and bonus

Available at: http://www.anp.gov.br/brasil-rounds/round10/resultados_R10/resultados_SPOT-T4.asp

For the PEM, which is the amount of activity that an investor would do in the area, the tender protocol also establishes minimums.

The signature bonus is the lump sum (in Brazilian reais) you pay to receive the block. As simple as that.

When the block is operating, there are four “participations to the government and third parties: (1) royalties; (2) special participation; (3) payment for the occupation of areas; and (4) landowner user fee, plus all taxes that any business would pay in Brazil. A good point to remember: many taxes are not levied on exports. Participation is the name given to the government take in Brazil.

Royalties normally amount to 10% of production. The area occupation fee is specific for each area, and fees to landowners are the equivalent of 1%. Special participation will depend on the volume produced and on what type of the area. For example, in lakes and onshore, if quarterly production is below 450 cubic meters of oil equivalent, special participation would be equal to 0. If quarterly production is above 2,250 cubic meters of oil equivalent, special participation would be above 40%.

Other facts:

–To be an operator you have to have at least 30% interest in the consortium;

— It is mandatory to drill or return the area after a period of time;

— The Exploratory phase has a maximum of years;

–A bond must be provided;

–Total term (after the declaration of commerciality) in Round 10 was 27 years, but this can be extended.

Conclusion

It is important – especially for foreign investors – to understand that Brazil is a different country from both other developing countries and wealthy countries. The bidding procedure is fairly transparent as is Petrobras management. Although corruption scandals pop-out all the time in the country, it is unheard of that Petrobras or its executives ask for money of foreigners. Additionally, dealing with ANP can be bureaucratic, but trying to bribe people there would be at least counterproductive, if not highly illegal.

Brazil offers opportunities not only for companies willing to drill, but for niche and service providers as well, who are in very high demand. However, it would be a natural and acceptable strategy to drill and export all O&G found, something that could make investors happy. An interesting presentation that summarizes the position of the government can be found here:

http://www.amchamrio.com.br/download/palestras/2011/1485_MagdaChambriard_ANP.pdf

Petrobras has a very important role in the country’s production and distribution. In fact, even after many years of market liberalization, Brazil is highly dependent on its NOC. However, this has never caused a problem with many different companies, including from different countries setting up in Brazil. They encountered and will keep encountering challenges, but the country is a great investment opportunity with no war, riots, bombs, terrorism, or corruption to get blocks: no real craziness! But, I am certain the main reason many investors are flocking to Brazil is the fact that after a long day in the office, they can have a coconut or a caipirinha in a kiosk near the beach!

About the author

Arthur Rodrigues is an attorney (RJ, Brazil and NY, USA) and academic focused on Energy, especially oil, gas, and biofuels. In Brazil, he worked for ANP and taught at the Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora. In the US, he worked for the University of Michigan and is currently working at the World Resources Institute. Contact information: arthrod@gmail.com

About Us

China Oil Trader™ strives to provide a holistic, globally-oriented analysis of Chinese oil and gas issues. In doing so, we often view multiple classes of commodities simultaneously and assess how they interact with each other. Our ultimate goal is to provide a focused source of fresh, creative, and anticipatory research for policymakers, investors, and others interested in China’s development as an energy and commodity superpower.